Velocity. Synonyms: swiftness or speed. In the case of this week’s readings, extremely slow mental velocity occurred for me, meaning it was hard to keep up. However, there was one continuous reaction I felt throughout the majority of the posts: disagreement (besides that of confusion, obviously).

I’ll begin with Fisher, so I can get him over with first. He discussed a lot of different topics that somehow intertwined throughout his piece. Some were fine, others were not, but a lot of the time I found myself wondering why does this even matter? He remarks in his conclusion that he was “concerned with the concept of technical reason and the way it rendered the public unreasonable” (392), which seems like a nice enough notion, I just guess I was (and am) lost throughout the essay on the impact technical reason was truly having on rhetorical discourse.

Now onto Porter. His main concept was intertextuality: “the principle that all writing and speech – indeed, all signs – arise from a single network… ‘the web of meaning’” (34). This turns into an argument that basically every written piece of art (and other works of art) take traces from other artworks, making them not entirely original. Again, my common question was wondering why this is important.

So, having stated that both Fisher and Porter (but especially Fisher) confused the hell out of me and left me wondering exactly why I read these pieces, let’s get into where I disagreed with these authors, and then maybe someone will be able to tell me what they hoped readers would be getting out of it and how I’m reading them the wrong way.

First Fisher, again.

My main issue with Fisher is his reasoning about why people may choose not to vote, which he uses as an example to distinguish between his new, narrative paradigm and the traditional, rational paradigm.

On 386, Fisher writes, “Persons may even choose not to participate in the making of public narratives (vote) if they feel that they are meaningless spectators rather than co-authors”. Now, this alone is fine and true. One of the main reasons people choose not to vote is because they feel their voice won’t be heard and listened to, so why even waste their time with it? However, Fisher then continues “But, all persons have the capacity to be rational in the narrative paradigm” (386).

This is where he loses me. My first thought reading the entirety of that sentence was that people have the rationale and capacity to vote in both Fisher’s narrative paradigm and the traditional, rational paradigm – just as they also have the capacity to refuse in both.

I disagree with what might be a key part of his paradigm, which is maybe why this example didn’t sit well with me. Fisher explains that in the traditional, rational paradigm, “rationality was something to be learned, depended on deliberation, and required a high degree of self-consciousness” (384) and that in his paradigm, there weren’t such demands. But, there should be, shouldn’t there? Rationality is learned, does depend on deliberation, and definitely requires a high degree of self-consciousness. If someone doesn’t have the mental capacity be self-aware, how can we expect them to properly use reason and logic? Don’t those two concepts go hand-in-hand?

Now that I have asked a whole lot of questions about Fisher’s own logic, we move once more onto Porter.

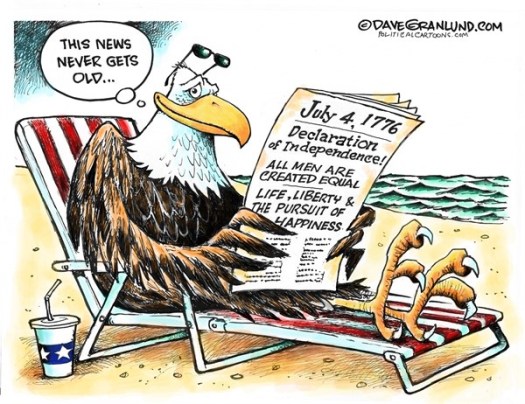

Porter is all about how nothing and no one is original, basically. When discussing the creativity (or lack there) of the Declaration of Independence, Fisher writes how “Jefferson was by no means an original framer or creative genius” but rather just “a skilled writer… because he was an effective borrower of traces” (36). If we’re going to go down that rabbit-hole, then absolutely nothing and no one is, was, or ever will be original and creative.

I argue that instead of that being the case, Jefferson was both original and creative. In order to write the Declaration, he had to weave all sorts of different traces together in a new way (making it original and creative, I argue, as it had not been done before). The dude took so many traces and wove them together that I basically lost count. I mean, he constructed traces from different nations that were literally a sea apart and somehow artfully merged those with traces from a colonial play (36)! How much more creative can one get?

Sure, people borrow traces all the time. People write or draw or paint in response to their surroundings, their time era, the current situations going on around them, or the art works of others that touch them and inspire their own work of art out of it (along with a lot more). Does that really make their work any less original or creative? I firmly believe there is a difference between blatant plagiarism and borrowing of traces.

Now, before I conclude this blog post, I’ll briefly touch on Ridolfo’s & DeVoss’ short article. I’ll be honest in that I don’t have much to say on it because I struggle to see how it connected much with this week’s other readings besides with the idea of rhetorical velocity. Rhetorical velocity is “a conscious rhetorical concern for distance, travel, speed, and time, pertaining specifically to theorizing instances of strategic appropriation by a third party” (Ridolfo & DeVoss).

Either Fisher or Porter (maybe both?) at least alluded to this idea, if I remember correctly. I suppose it could be one writing technique to use, but I feel it’s not the most important to apply. Instead, I would argue that writing to your readers of today is a better idea. And then, if you construct something as original and creative as the Declaration of Independence, maybe the readers of the future will enjoy it just as much.

Velocity also implies a particular vector — a direction. In that sense, it’s a miracle anyone had any velocity at all when it came to reading these texts. Personally, I felt like I was weaving in and out of my metaphorical lane like a drunk driver, especially while reading Fisher.

On the topic of Fisher’s article, I’m not sure I can argue against your disagreement with him, because I share many of your attitudes. One idea in particular that I am also resistant to is that rationality is learned, but narrative isn’t. You bring up that Fisher says, “in his paradigm, there weren’t such demands. But, there should be, shouldn’t there?” I would answer: yeah, there should be. Narrative is absolutely learned, just like rationality. The way you frame your personal narrative is based on your culture, your nationality, your religion, etc. All of these things are human institutions that teach you their stories. If narrative wasn’t learned, if it was somehow instinctual, then everybody’s narrative would be the same. But obviously that isn’t the case.

As for the usefulness of Fisher’s article: I suppose that it’s useful to know that rationality isn’t really all there is to decision-making. When people appear to be irrational, the truth is that they *are* being rational within the framework of their own narrative. Fisher quotes somebody in his article who says, “Voters aren’t stupid.” I believe that. Voters aren’t stupid — their voting patterns are based on a story that aligns with a narrative they like. But again, the complexity of Fisher’s argument really loses me, so I don’t quite know if this is what he’s going for, even after our discussion in class.

I was much more “on board” with Porter’s article, though. And in that context, I do disagree with you in some ways.

I don’t think that Porter meant to argue that nobody was truly creative — just that not many were truly original, even those we consider great writers. When he gives the example of Thomas Jefferson drafting the Declaration, he does not take away from his personal accomplishment as a writer, the beautiful craft evident in his writing, or the incredible impact that his document had.

In your post, you are tend to use the words “original” and “creative” in the same stroke. I would make an important distinction: a writer can be spectacularly creative, but rarely or not at all original. And, furthermore, it isn’t particularly important that they are original.

If a writer assembles many different pieces from many different sources into a collage, they will be judged not necessarily on the content of that collage, but rather how well they have made those pieces fit together. And what’s more, outside of blatant, unethical plagiarism, nobody would call them out for being a fraud. This is because, in many cases, it’s only blatant and unethical when its uncreative. But the fact of the matter is that, considering the 7 billion+ people on the planet, nearly everything you will ever write has been written before, in some form or flavor. It is merely your obligation as a writer to know when it is appropriate to write old words anew, to address a new audience in a way they will appreciate. Creativity and the wherewithal to know what words came before you, not originality, is the mark of a great writer.

This distinction between creativity and originality might seem like I’m splitting hairs, but I would argue the distinction is actually quite important.

I think one of the ideas of Porter’s article is that we tend to romanticize writers and writing. We think of writers as these lone wolf geniuses that sit alone in their smoking room, staring at a blank piece of parchment with quill in hand, waiting until their muse finally speaks to them and they spontaneously produce content the likes of which the world has never seen. We think this is always the case. And when people go and try this for themselves — they go into their own study, stare in silence at their own blank piece of paper, and wait for the words to come — they are disappointed when nothing happens. Or, maybe they do write something, but then realize, “Hey… this is remarkably similar to [XYZ document],” and, in light of such a realization, deem their writing to be totally worthless. Still others do not write at all, convinced they cannot come up with anything new.

When these things happen, they chalk it up to their own lack of talent, of inborn ability, which couldn’t be further from the truth. I see this ALL THE TIME with students, especially freshmen, as a tutor in the Writing Center. They often get discouraged with writing, decide they don’t like it, and avoid it whenever possible.

Usually, the truth is that they simply haven’t been in the “Burkean Parlor” for long enough to create anything new; in other words, they haven’t been a part of the conversation of their genre for long enough. But here’s the kicker: you have to contribute to your conversation in order to be a part of it. And to contribute, you are inevitably going to end up saying things that have already been said. The longer you listen, and the longer you contribute, the closer you get to being able to add something new.

But even veterans of these conversations are re-discussing things that have already been said; and often, when “new” information is brought in, it’s because that person was inspired by another field (in other words, they allowed themselves to be intertextual).

And y’know what else? It doesn’t even matter that a piece of writing isn’t new. It can still be high-quality, relevant, and even necessary. That’s right: redundant writing is necessary.

So, given that originality is so difficult that it’s practically impossible for the vast majority of people, even those we consider geniuses and prodigies, can’t you see the problem with telling budding, potential writers that the only way their writing will have any value is if it’s unique? It’s discouraging, and has a suppressing effect on the creation of knowledge.

This happens in all fields involving communication (which is to say: all of them). The vast amount of information you consume is unoriginal.

–Creative Writing: Your story sounds like X author, with hints of Y and Z. It’s unoriginal and therefore without value.

–STEM Fields: Your study incorporates research from the experts in your field, and even if your experiment isn’t exactly like theirs, it arrives at logical conclusions that are in line with previous thought. Or perhaps you arrive at a different conclusion — but the fact is that you’re still using existing studies as a baseline comparison.

–Heck, even YouTubers: There is a general, pre-established pattern to successful videos that keep a watcher’s attention. Many videos borrow clips, music, and graphics from other sources.

Despite the fact that these things are unoriginal, it doesn’t take away from their craft, their entertainment value, their usefulness, or their relevance.

That’s why the distinction is so important. When, as a culture, we fetishize originality, we discount creativity. If people were less concerned with being original, I think we would see truly amazing works of writing coming from people and places that we wouldn’t typically see it.

That’s just my two cents.

P.S. Sorry for the essay of a comment. I promise I’ll exercise more restraint in the future.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Abby,

I love your conclusion as it uses the Declaration of Independence as a model for creativity and origionality. You really want to stick it to Porter with that.

I think that Porter would actually agree with you about Jefferson’s being creative. He only wants us to realize, as Tyler mentioned in his blog, that creativity and originality do not create something out of nothing. The funny thing to me is that he even has to say it. We recognize this principle in any other feild. It is the conservation of matter for litterature in a sense– the conservation of narrative, to bring Fisher into the discussion.

For me, it almost seems silly to have this discussion because it is like telling fellow lego enthusiasts, your not going to build something out of nothing. Somebody already created the bricks. Infact, some of these bricks ave been used in the past in other builds. For literature and rhetoric, the medium is not letters or words. It’s words, phrases, ideas and narratives (I think I said that in my post). And just as some lego peices were fabricated to be specific parts such as suits a theme in a particular set of legos, so some components of discours are recognizable as another person’s idea. Both can still be used creatively.

It’s a bit insulting that Porter believes that witers need to ve told more than lego masters do that they don’t need to reinvent the wheel– that they can incorporate an existing one. And yet, I think he’s right. We’re often such romantics, such purists that we need to be told.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ugh. Sorry for all the typos. I typed this on my phone and missed many errors.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Abby, here’s that link we talked about in class today — https://www.ted.com/talks/kevin_allocca_why_videos_go_viral

LikeLiked by 1 person